Tamayakin’ initiative

Tamayakin’ initiative

Carbides in Iron and Steel Materials (2) - Solid Solution and Precipitation

Return to list

Return to list

Overview.

In ordinary steel materials, quenching causes solid solution of carbides and martensitization, and tempering causes precipitation of fine hard carbides, which improves wear resistance and toughness.

01 Solid solution of carbides during quenching

The purpose of quenching in steel is to heat the steel to the austenitic region so that the carbides are sufficiently solid-soluble. The amount of solid solution of carbides is governed by the quenching temperature and the heat holding time, with the former having a much greater effect.

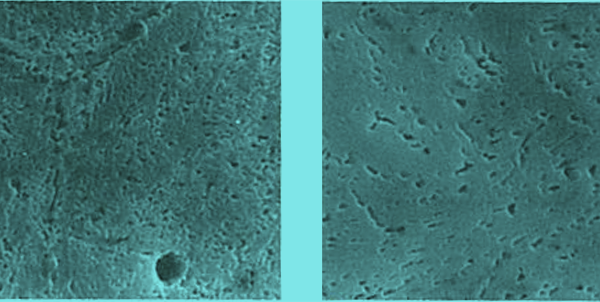

However, not all carbides are solidly dissolved by quenching. Especially in the case of highly alloyed steels such as die steel and high-speed tool steel, there are always some unconsolidated carbides. As an example, the figure below shows the relationship between quenching temperature, carbide content and hardness of various types of high-speed tool steels. These remaining carbides are called Unsoluble carbides and that high hardness cannot be obtained if the solid solution of the carbides is insufficient.

02 Deposition of carbides due to tempering

Carbides are solidly melted by quenching and transformed by tempering Secondary carbides secondary carbides. This precipitation of secondary carbides increases the toughness of the fabric and, depending on the steel grade, hardens it and improves wear resistance.

The above figure shows the change in the amount of carbides in 13Cr steels of different carbon contents quenched at 950°C and tempered at 200~700°C for 60 minutes. The amount of carbides is the same level as when an nealed at 600°C or higher.

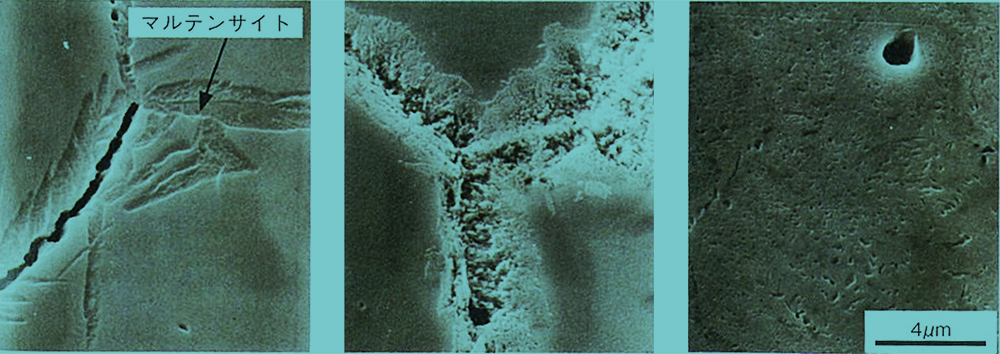

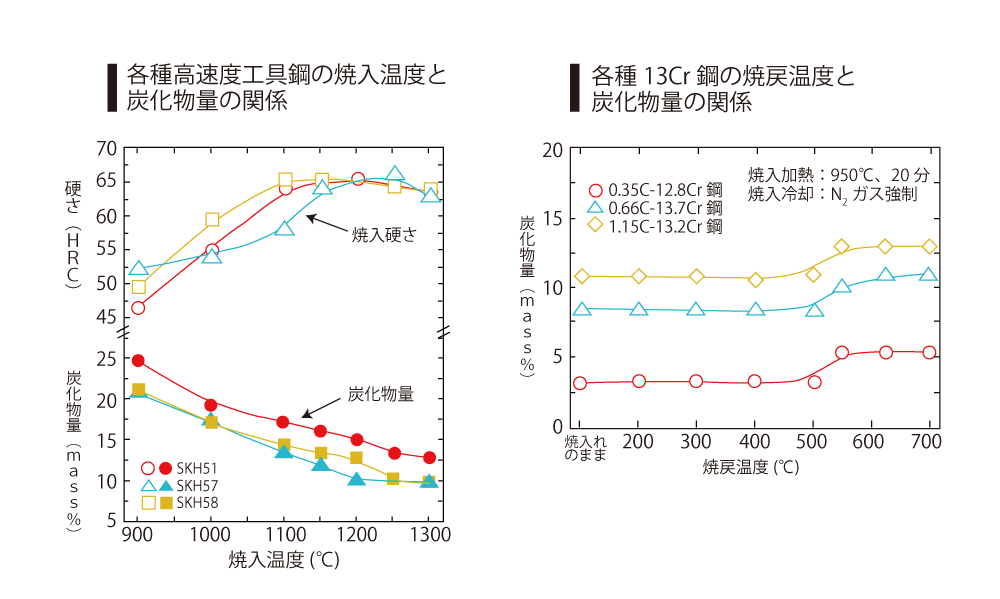

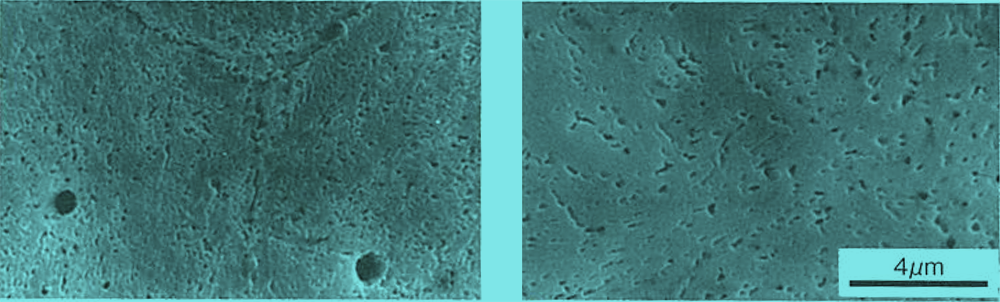

As an example, the figure below shows the precipitation of secondary carbides resulting from tempering above 500°C. The higher the tempering temperature, the more active the precipitation of secondary carbides. In the case of 0.66C-13.7Cr steel, a large amount of residual austenite was generated by quenching, and in the tempering at 500°C, martensitic structure is observed around the grain boundary, but no secondary carbide precipitation is observed. This suggests that if residual austenite is present, martensitic transformation occurs first by tempering, and secondary carbides precipitate by the next tempering.

Precipitation of secondary carbides in tempered 0.35C-12.8Cr steel (quenched at 1150°C)

Precipitation of secondary carbides in tempered 0.66C-13.7Cr steel (quenched at 1150°C)